What is reharmonization? Michael Emenau explains the musical theory behind reharmonization and shares tips on how to reharmonize a song using SOS by Avicii.

What is Reharmonization?

Reharmonization is when you substitute or change chords in a song while keeping the melody the same. It allows you to change the harmony of a song while still retaining the original melody. There are different reasons why you may want to reharmonize a chord progression. For example, reharmonization is useful for:

- Remixing or creating variations of existing songs

- Giving the song a different personality

- Personalizing a song to make it your own

- Making the song more harmonically complex and interesting

- Giving the song a “jazzy” feel

- Making the song sound fresh or unique

- Changing the mood or feeling of a song

- Figuring out new ideas for other songs

- Playing a song in a new way that’s less boring

To understand reharmonization further, you must first know how harmony works. In its simplest form, harmony occurs when two or more notes are played simultaneously. For example, the chords that support a single line melody creates harmony. Generally, the underlying chords (chord tones) will contain the strong melody notes (notes that either repeat in a bar or are longer than other notes). For example, playing a C major chord and using the notes C, E, or G in the melody will create harmony.

The interaction between melody and harmony gives the song richness and flavor. However, you can change the flavor of a song by substituting one or more chords that still work musically with the melody. For example, you can replace chords that share common tones without completely changing the original song. It’s an excellent technique that gives an existing song a different sound and a personal touch!

[yuzo]

Why Reharmonize a Song?

Reharmonization can dramatically change the mood and character of a song. Changing the underlying harmonies can bring new life to your music by adding varying degrees of tension and harmonic color to your chords. For example, you can transform a happy pop song into a sad song (or vice versa).

Why would a musician want to change the chords in a song and not change the melody? The melody is often the most recognizable and catchy part of a song. It’s the part most listeners latch onto and sing or hum. By changing the melody, you risk altering the most identifiable aspect of a song.

Whereas, substituting the harmony chords is a much safer way to modify the sound without completely changing the song. This technique allows the listener to hear the same melody they’re familiar with in a fresh, innovative way.

For example, the original chords for Jingle Bells are:

C – C – C – C7

F – C – F – G7

In a reharmonization, the melody notes stay the same, but some or all of the chords are different. In the example below, I transposed the chords for Jingle Bells to the relative minor:

C – Amin – Fmaj7 – Emin7♭5/A7

Dmin7 – Cmaj7 – B7♭5 – E7#9 – Amin

Reharmonization Techniques

There are many ways in which you can find chords that support a melody. Here are three common reharmonization techniques:

1. Relative Minor or Major Substitution

Every key has a group of chords that sound good together. These chords are called relative chords. Each chord in the scale will have either a relative minor or major chord that complements it. For example, A minor is the relative minor of C major.

Relative chords sound good together because they share two common notes and are based on the same scale. A common way to reharmonize with relative chords is to swap the (I) chord for the relative minor (vi) chord (or vice versa). For example, in the key of C major, the (I) chord is C major, and the (vi) chord is A minor.

To find the relative minor chord, start on the sixth scale degree of the major scale. For example, count up to the 6th note of a major scale and build a minor chord from that note.

To find the relative major chord, start on the third scale degree of the minor scale. For example, count to the 3rd note of a minor scale and build a major chord from that note.

In almost any case, you can exchange the relative major and minor chords in a song. The feeling will change, and the melody note may sound a little off, but you will still be in harmony.

Here is a chart to help you find every relative key without having to count scale tones.

| MAJOR (I) | RELATIVE MINOR (iv) |

|---|---|

| C | Am |

| Db/C# | Bbm/A#m |

| D | Bm |

| Eb | Cm |

| E | C#m |

| F | Dm |

| F#/Gb | D#m/Ebm |

| G | Em |

| Ab | Fm |

| A | F#m |

| Bb | Gm |

| B | G#m |

2. Reharmonizing with Diatonic Chords

Every major and minor scale has seven diatonic chords. They are chords formed from the seven notes of any particular scale.

When reharmonizing a song, you can experiment with these chords in any combination to hear how they sound. Some chords will sound more “harmonious” than others, some will sound bad, while others may bend your ears in new and interesting ways.

Working out the seven diatonic chords for any scale can be tricky at first. However, there is a simple formula to help you build a diatonic chord from each note in the scale.

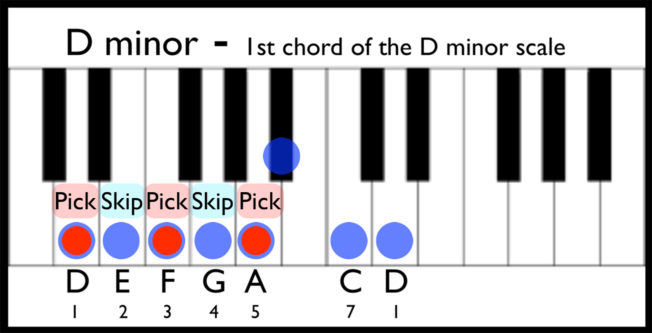

Build a diatonic chord by stacking thirds from the root of the scale. For example, take any note in a scale, then count up two notes and four notes in that scale. I think of it as pick a note, skip a note, pick a note, skip a note, pick a note.

For example, the illustration below shows the note names for D minor, and the numbers show the distance each note is from the root. You can see the D minor scale has the notes D – E – F – G – A – B♭ – C. Start with the root note (D), skip (E), pick (F), skip (G), and pick (A). This pattern gives you the first diatonic chord of the D minor scale. The notes for this chord are D – F – A, which makes a D minor (Dmin) chord.

This pattern works for every note of the scale. Let’s try it again to work out the diatonic chord for “E.” Start with the note (E), skip (F), pick (G), skip (A), and pick (B♭). The notes are E – G – B♭, which makes an E diminished (E°) chord.

Follow this logic to work out the remaining diatonic chords. The seven diatonic chords in the key of D minor are Dmin, Edim, Fmaj, Gmin, Amin, Bbmaj, and Cmaj.

Finally, once you work out all seven diatonic chords in any scale, you can play with them to reharmonize a song.

3. Common Chord Tone Harmony

A more harmonically advanced way to find chords that support your melody is to look into the chord structure. You can use any chord which contains a melody note to reharmonize. For example, you can substitute a chord that has one of the same notes in your melody.

However, this technique does not guarantee it will sound good. But it will open the door to many new chords and chord combinations you may have never thought of using.

For example, if your main melody note is a “G,” try figuring out which chords also have a “G” note. Any chord that contains a “G” is a possibility. Here are a few examples:

Major Chords

Gmaj (G – B – D)

C maj (C – E – G)

E♭maj (E♭ – G – B♭)

Minor Chords

Gmin (G – B♭ – D)

Emin (E – G – B)

Cmin (C – E♭ – G)

Diminished Chords

C#dim (C# – E – G)

B♭ dim7 (B♭ – D♭ – E – G)

Augmented Chords

E♭ Aug (E♭ – G – B)

B Aug (B – D# – G)

Minor 9 Chords

Amin 9 (A – C – E – G – B)

Fmin 9 (F – A♭ – C – E♭ – G)

With chord tone harmony, it’s not how one chord harmonizes with one melody note. Instead, it’s how groups of chords move around a progression and how they interact with the song in general. It’s an excellent technique for discovering unique ways to transform your music. You can even take chances and incorporate seemingly strange chords into your music. Remember, if it sounds good, USE IT!

Reharmonizing SOS by Avicii

Let’s look at reharmonizing the first part of the song SOS by Avicii.

Here are the original melody and chords from SOS. Please note, I have transposed them to D minor to work with the diatonic chord examples above. The original chord progression is:

Dmin – Amin – B♭maj

B♭maj – C maj – Dmin

Using the diatonic chords of D minor, I will show you two reharmonized examples of SOS.

Example One: I started the chord progression on a B♭maj chord and ascended through the scale in each section. The new chord progression is:

B♭maj – Cmaj – Dmin

Gmin – Amin – B♭maj

Example Two: I started on Fmaj, which is the relative major of D minor. I also based the remainder chords on this major feeling. The new chord progression is:

Fmaj – Cmaj – B♭maj

Amin – Gmin – B♭maj

Again, it’s your ear that’s the final decider. Play around with the melody and experiment with the diatonic chords in a different order until you decide what chord progression is right for you.

Conclusion

Reharmonization is an incredibly valuable tool. You can use it to improvise or create a new, reharmonized version of a song. Reharmonizing music also helps to develop your ear and understanding of music theory.

As you delve more deeply into reharmonization, you may also find that sometimes a melody note conflicts with the chords. When this happens, be flexible and try changing a chord to a different flavor. For example, try changing the chord to a minor, major, diminished, dominant, etc. You can also try lowering or raising the melody note a semitone.

Your ears should be the final judge, not your eyes or any rules about harmony. Remember, music theory is a tool for expanding your creative process – it’s up to you to make it beautiful.